Where the

Earth Quakes

Sibillini Mountains, March, on going

Among the

communities of the central Apennine

mountains, the ancient legend of the Sibyl

is told.

A woman, good fairy, seer and enchantress,

who lived in a cave on the

top of the mountain that today is named after her: Mount Sibilla.

According to

the local tradition, the Sybil provoked

an intense earthquake in the town of

Pretare.

The fairies, her maids,

remained to dance in the

village all night,

beyond the time allowed for

the return to the cave. The priestess was a

reference for the inhabitants of the mountains and for anybody who went up to

the cave to meet her.

Since 69 AD many people are reported to have ascended to

meet the priestess who predicts the future.

In this land pagan and religious

cults have intertwined. Today the cave is inaccessible, since 1960 the access

tunnel has completely collapsed.

The

story ends and the legend begins.

A desert called Foce

Sibillini Mountains, Marche

Desert in Latin has a double meaning: abandoned and neglected by people or left uncultivated. Foce di Montemonaco, a small village in the Appennine Mountains, in the heart of Italy, was severely ruined by the 2016 Central Italy Earthquake.

Nowadays only 5 people are still living in Foce and on the last summer no tourists came. Three young Romanian guys use to work in Foce as seasonal lumberjacks.

The state of abandon of this place in the middle of nothing reflects the landscape f chopped woods cut by these three workers, who themselves had to leave their home to find a job that no Italians are willing to do.

The lumber industry still survives, despite

the drop of productivity due to the earthquake.

Foce can be reached through a single road

that enters a very narrow gorge and stops right in front of the slopes of Monte

Sibilla and Monte Vettore. From there you can continue only on foot.

In the Aftermath

Sibillini mountains, Earthquake, ongoing

A year has passed since the

severe earthquake that hit central Italy.

Broken mountains, lands almost one meter crumbled, collapsed buildings,

sheds and stalls with broken roofs, rivers that have changed course, roads

that have disappeared and a land that continues to shake.

The movement of the earth has

also caused a movement of those who lived there.

The mountain community of the Sibillini Mountains is composed of many villages scattered over a very large territory.

Some are gone, someone tries

to resist. The reconstruction will last 10-15 years

and the oldest will no longer see their homes. But citizens are trying hard to

regain possession of their lives and their land.

This series is part of the

collective documentary project Lo

stato delle cose.

Apennine mountains, on going

Tempo di ritorno / Return period

tèmpo [lat. tĕmpus, di etim. discussa]

s. m.

di ritòrno [da

ritornare]

s. m.

1 Stimatore della ripetitività del fenomeno

sismico.

2 Movimento per ripensare i luoghi ai margini e

ripartire.

Return (lat. tempus, of etim. discussed)

period

1 Estimate of the likelihood of an earthquake.

2 Afterthought of marginal places.

A seguito di un precedente lavoro di documentazione per Lo Stato delle cose dei

luoghi e delle comunità colpite dal terremoto, sentiamo

l’esigenza di operare nelle comunità dall’interno scegliendo

di utilizzare il video e la fotografia non come strumenti di una

nostra narrazione, ma come strumenti che diano voce alla

narrazione della comunità stessa.

After a previous documentary project for Lo Stato delle cose dealing with communities affected by earthquake, we feel the need to move on withto use video and photography as tools that give voice to the community itself.

Abitare temporaneo - abitare a lungo termine

La ricerca si sviluppa all’interno di tre comunità montane

dell’Appennino coinvolte dal terremoto del 2016, Montegallo,

Arquata del Tronto e Amatrice, luoghi fragili sia da un punto

di vista fisico sia politico. Qui il processo di spopolamento e

abbandono già in atto è stato accentuato dalle conseguenze

del terremoto. L’urgenza di indagare queste realtà

periferiche, ma peculiari del contesto italiano, ambisce

a lavorare sulla rottura della geografia del paesaggio

che si è creata dopo il sisma. Le comunità sono rilocate

in Sae (Soluzioni abitative di emergenza), strutture

prefabbricate, smontabili e riconvertibili che si legano al

nucleo abitativo originario in modo differente a seconda

delle diverse modalità di ricostruzione. Dato il tempo

medio di ricostruzione dei borghi storici che varia da 5 a

10 anni, nel lungo periodo le aree Sae da contesti abitativi

emergenziali diventano veri e propri insediamenti dove

l’abitare temporaneo diventa permanente.

From temporary to permanent dwelling

The research focuses on three communities of the Apennines involved in the 2016 earthquake: Montegallo, Arquata del Tronto and Amatrice. Here the process of depopulation and abandonment has been accentuated by the consequences of the earthquake. We aim to investigate the way these communities recreate a new geography of the landscape after the earthquake. The communities are relocated in Emergency Housing Solutions, prefabricated structures, demountable and reconvertible that are linked to the original housing nucleus in different ways according to the different reconstruction methods. Given the average time of reconstruction of the historic villages (ranging from 5 to 10 years), in the long run the Sae areas from emergent housing contexts become real settlements where the temporary dwelling becomes permanent.

Emergency housing under construction (Sae), Montegallo, Marche, december 2017

Emergency housing under construction (Sae), Montegallo, Marche, december 2017

The project purpose and the working method

house / home

Le case Sae (house) diventano così i luoghi di un tempo e di uno

spazio sospesi dei quali gli abitanti si riappropriano solo grazie alla

ri-costruzione attiva della dimensione simbolica e identitaria della

casa (home). Il processo di ricostruzione attivato dalle istituzioni,

impositivo e assistenziale, impedisce invece la ricomposizione

di un sé individuale e collettivo che può avvenire solo con un

processo di ricostruzione attivo e partecipato. La ricerca intende

muoversi proprio in questo spazio di incapacità di risposta da

parte delle istituzioni ai reali bisogni dei cittadini, innescando un

processo attivo di rielaborazione dell’abitare del passato attraverso mappe geografiche della memoria.

Si chiederà prima alle persone

rilocate nei nuovi insediamenti di raccontare attraverso un disegno

l’abitare del passato, sia quello intimo della propria casa sia quello

in relazione al contesto. Il disegno-racconto, che è una mappa

della memoria e dei ricordi, sarà realizzato e filmato nella nuova unità

abitativa emergenziale. Il video, che ha una

durata variabile corrispondente al fluire della memoria, è la raccolta

del momento di riappropriazione dell’abitare, quando l’abitazione

torna a essere casa.

La seconda fase del lavoro avviene invece

in un contesto comunitario. Le mappe della memoria saranno

prima interpretate e poi ricucite insieme agli abitanti, sia in senso

simbolico sia fisico, nella mappa collettiva.

The inhabitants of the Sae- Emergency housing (HOUSE) have to reappropriate the symbolic and identity dimension of the HOME through an active and participated process. Instead, the post-earthquake reconstruction process by the institutions prevents the reconstruction of an individual and collective self. The research aims to fill this gap, giving voice to citizens and triggering an active process of rielaboration.

People relocated to new settlements will be asked to tell through a drawing their way of living, intimate and collective, before the earthquake.

First of all, the people relocated to the new settlements will be asked to draw the story of their way of living in the past. The drawing-story / map of memory will be realized in the new emergency housing unit and filmed by the authors. The video, which has a variable duration corresponding to the flow of memory, will record the moment when the house returns to being home.

The second stage expects the involvement of the inhabitants of the Sae who will stitch together the maps with the help of a psychologist.

The research project

Call for Projects Abitare

The project Tempo di ritorno

was selected among the 50 finalist projects of the call Abitare: sette sguardi sul paesaggio fisico e sociale dell’Italia di oggi promoted by MiBACT in collaboration with La Triennale di Milano and the Museum of Contemporary Photography.

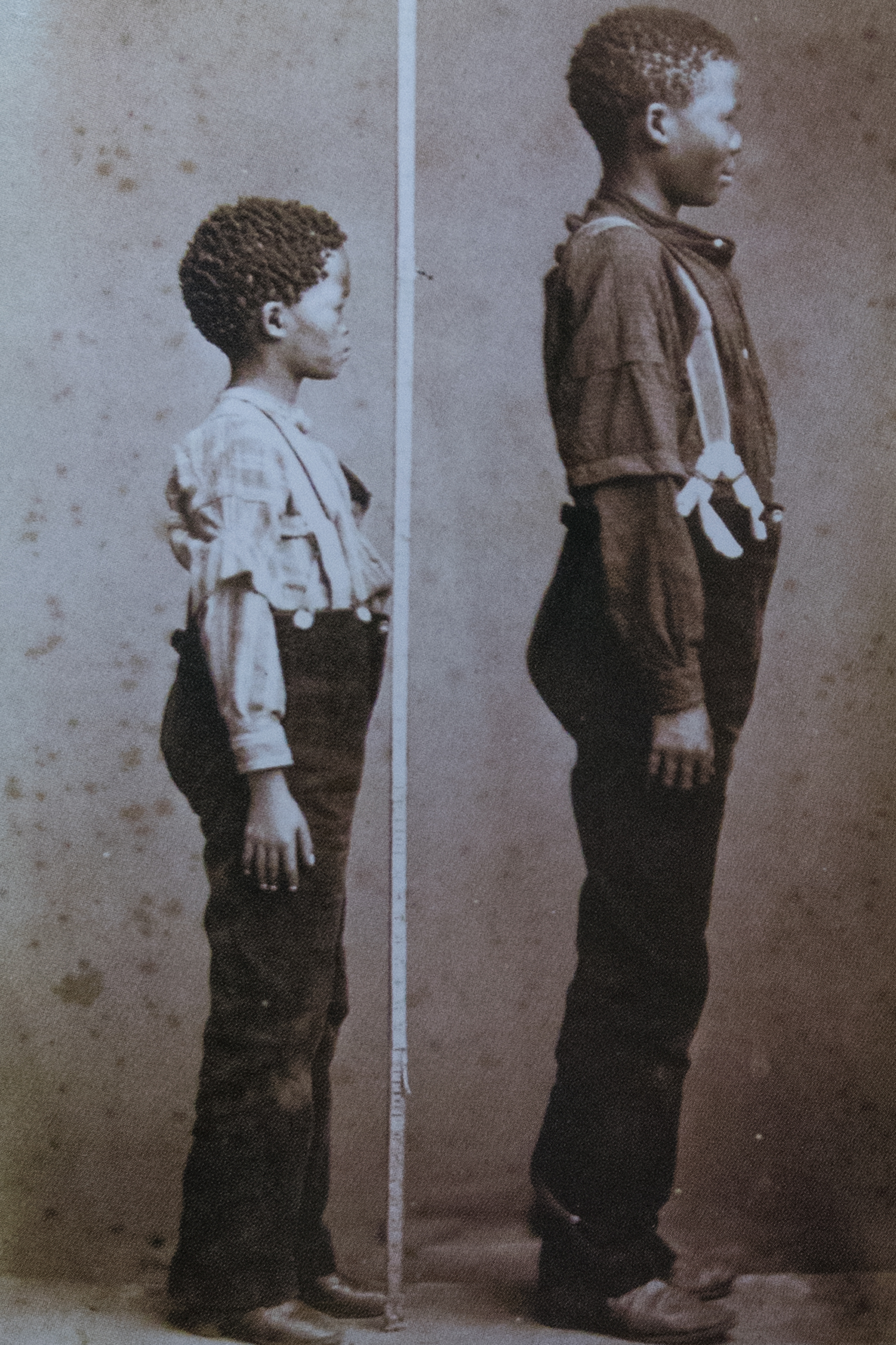

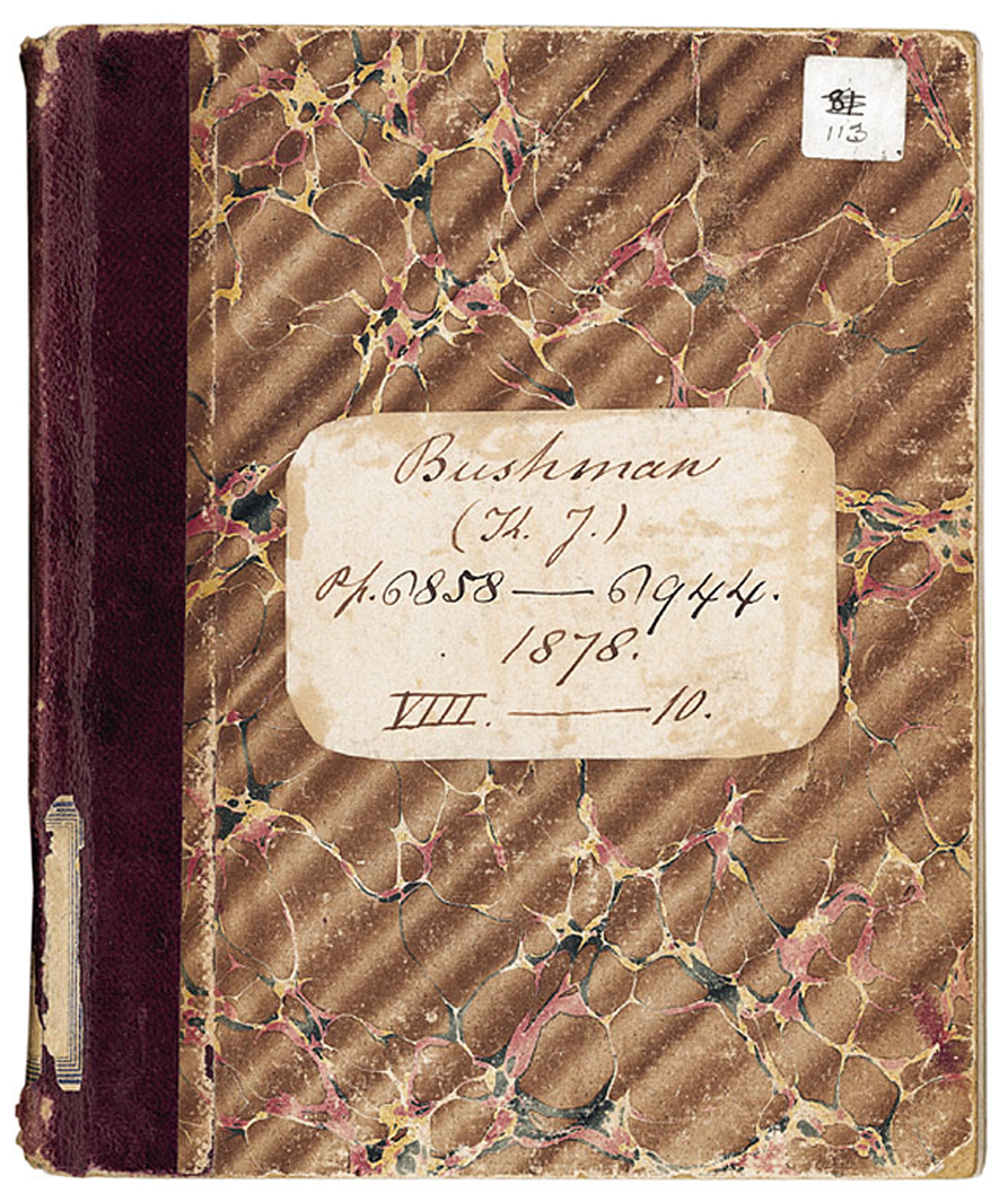

Omang

Botswana, CKGROmang in Setswana language means National Identity Card which is something that claims who you are and where you live. The project aims to use the omang as a metaphor to tell the story of the Bushmen of Kalahari who are forced to live within boundaries established by the government of Botswana. The Bushmen have been living in the Kalahari Desert for 20.000 years. In 1961 the Government of Botswana established the Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR) to protect some Bushmen communities. At the beginning of the 80s the discovery of diamond mines inside the reserve led to the forced displacement of the Bushmen communities and to the dismantling of their homes, schools, hospitals and water supply. Nowadays most of the Bushmen live in the resettlement camps outside the CKGR. While the tourists can enter the reserve, the Bushmen are forbidden to access the CKGR and they can’t hunt and gather in their own land. A community of 3.000 Bushmen lives in New Xade, a resettlement camp placed about 40 kilometres outside the CKGR. Alcohol, HIV and unemployment are tearing them apart. Since 2002 the Bushmen took the Government to the Court to claim their right to come back to their ancestral land.

Irene Fassini

All the historical images are taken from the book Claim to the Country. The Archive of Wilhelm Bleek and Lucy Lloyd by Pippa Skotnes.

Exhibition:

http://www.museomaga.it/mostre/138/PREMIO_RICCARDO_PRINA